Comprehensivism is the practice of considering with ever increasing depth and breadth more and more of Humanity’s great traditions of inquiry and action to better comprehend how our worlds work and how they change so we might all live more effective lives. In this practice, as each explorer reflects on the value of their independent and group learning, they will from time-to-time identify ideas that they think should be collaboratively examined.

Collaborating for Comprehensivism aspires to engage every participant in organizing ideas for the group to explore. We think this kind of engagement of participants is necessary to activate the full potential of the collective intelligence of the group.

To exemplify this aspiration, we will share and explore an idea that we think should be collaboratively examined. Let’s investigate the idea that story may play a fundamental role in all traditions of inquiry and action, in the practices of a comprehensivist, and in our lives.

Is Story Fundamental in Our Lives?

Oral and visual storytelling is known in prehistory. Children love picture books that engage written and visual language. Movies and theater continue to be valued even during global pandemics. We are all moved by good stories. Story is clearly important to our lives, but is it fundamental?

Jacques Hadamard collected evidence that Einstein and others think non-verbally. Mind and thought may extend beyond the reach of story into the realm of the ineffable, beyond what can be described. How might we circumscribe the part of our lives that is about story?

Let’s consider the distinction between what happened and what we say about what happened. The word “fiction” means a construct or invention. What we say about what happened is necessarily an invention of language constructed to report to self or others a story about what happened. That is to say, all description is constructed and invented: it is a fiction.

Story is what is said about what happened, what is happening, or what may happen. All stories are necessarily fictitious even when they adhere closely to the Truth of what happened. In fact, non-fiction is, in a way, more hypocrisy and deception than fiction because it falsely pretends that there is a way of storytelling which somehow provides a privileged access to Truth.

No story, not the most careful scientific report, nor the finest mathematical or logical proof can ever tell us exactly what is, nor exactly what happened. Why? Because, at its best, such reports are symbolic constructs attempting to represent and intimate what is. No description can ever report exactly what happened: that was already lost to the mists of history and the foibles of perception even if your scientific notebook is meticulous!

Arnold Weinstein uses the evocative phrase “fiction of relationship” to describe both the literature that discusses human relationships (family, friendship, business, romance, and more) and, as Weinstein puts it, “the notion that relationship itself may be a fiction”. We might glean that our stories (our “fictions”) about relationship are our principal tools for understanding.

It could be that the basic association in a relationship is the fundamental unit of knowing or understanding. Then an algebraic form to characterize a dawning understanding, an apprehension, might be the relationship aRb, meaning a is associated with b through the relation R. Since the relation R is a construct, Weinstein’s view that relationship may be a fiction seems apropos. Systems of such relationships would form a story. Knowledge seems to be intimately connected to story in this way.

In more human terms, a person is essentially defined by their relationships to place, people, history, values, passions, inquiries, and initiatives. In these terms Weinstein calls fiction of relationship the “voyage to the other”. In this way his expression addresses the poignancy of the basic issues of our lives.

In sum, we have a phrase that gets at fundamental aspects of our lives and our basic knowing in the world. The stories we tell are a fiction of relationship. Our lives themselves are a fiction of relationship. Our best languaged way of getting a vague grasp of the wisp of reality is a fiction of relationship.

Let’s take another tack at seeing story’s allegedly fundamental role. If the great traditions of inquiry and action encompass all human knowledge, how does story fit in each tradition?

It is possible to live isolated in the woods and to have great thoughts and build great artifacts, but unless an archeologist discovers your work and manages to piece together enough clues to interpret it astutely, no one will know about it and it cannot contribute to the accumulated wisdom of humanity. Traditions are passed on from person to person. They must be communicated. A tradition necessarily entails communication.

Any way of parsing and communicating experience forms the basis for a tradition. Aggregates of communicated experiences can be organized to form an approach, a way of thinking, a subject, even one’s life’s work. A teacher or their adherents may organize these stories to formally establish a tradition. Of course, any given collection of communicated experiences may dissipate on the scrapheap of yesterday’s babble that didn’t coalesce into something transmitted from person to person.

When our communicated experiences arrange themselves into something that gets passed on, they form the storyline of a tradition. In a very important sense, these stories form the great mythology for each tradition’s cosmogony and cosmology. In this way, story seems fundamental to all traditions of inquiry and action.

In Joshua Landy’s interpretation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Gay Science”, he argues that each of us should “turn our life into a work of art”. Landy adds, “art makes our life beautiful if we tell it as a story”. I hear Landy suggesting that our life should be constructed as an artwork and shared as a self-affirming story. In our language, each life would be presented as a tradition which others may then build upon.

When we tell the story of one of the great traditions of inquiry and action (which might be a story of our own life presented as an artwork) or when we compose a story weaving threads among several traditions, we regenerate Humanity’s cultural heritage bringing some of that wisdom forward. It could be that story is the warp and woof of the great traditions of inquiry and action, the fundamental structure upon which we build the knowledge of a comprehensivist.

Is story fundamental to our basic understandings? Is story fundamental in our great traditions of inquiry and action and in our comprehensivity, our state or quality of learning that is broad and deep? Is story fundamental in our lives? If so, how so? If not, why not?

What is the Role of Story in Our Lives?

In Dame Marina Warner’s subtle but profound presentation on “The Truth in Stories”, she shows how the fabulist (storytelling) imagination is a form of inquiry. Fantasy, fairy tale, and mythology present, in fact, questions about how things might be, questions about alternative ways of being. Warner says, “The inquiry a story mounts may also take a speculative form: offer an hypothesis, or a set of interlocking and often contradictory hypotheses. This is the enterprise of fantasy.” In Marina Warner’s able mind, the Truth of the fabulist imagination stands next to the methodologies of science as a way of exploring hypotheses!

This might lead us to an important corollary: assertions are a disguised form of question and ought to evoke a state of wondering: Could it be? How might it be? In what situations might it work out that way?

I think Warner’s subtle but penetrating point is that stories always and only present “The Truth” of wondering and inquiry. These Truths of the fabulist imagination may sometimes be more penetrating than what can be disclosed by traditions taking a “neutral” stance including government reporting, journalism, biography, history, and even science.

For our inquiry into the role of story, Marina Warner’s insights suggest to me that the great traditions of inquiry and action and their stories are not imperial impositions for us to adopt like vassals, but instead they are questions that should fill us with wonder: What Truths live here? Which of these wonders might apply in our worlds? How can we make sense of this?

For our comprehensivity, the stories from many traditions of inquiry and action can aid our wondering about the possible ways to organize a human mind and a human life. This archive of wonder and wisdom in the great traditions gives us the tools needed to broaden our understanding of it all. This realization reinforces the insight that comprehensivists ought not dismiss any tradition without wondering about the worlds it might open for our consideration.

(see Marina Warner’s essay “The Truth in Stories”)

To dig deeper, we might look at story through the lens of some theories (which are simply traditions held in high esteem by our culture). Consider Claude Shannon’s 1948 contribution of information theory. It provides a powerful model for communication at a fundamental level. Is a bitstream a story? Yes: at minimum it is the story of getting this message from here to there. But neither Shannon nor his successors in the tradition of information theory have mathematized interpretation. Interpretation is essential to story: both for the teller and the listener. So, we will need a more powerful theory to operationalize story in our lives.

In the theory of symbolic interaction of George Herbert Meade, our minds, our selves, and our behavior are seen as formed by our interpretations of symbols informed by our accumulation of social interactions. Indeed, our thinking and actions are seen as simply the product of our lifetime of evaluated symbolic interactions. Perhaps, we already knew that mind, self, and behavior were all inextricably linked to experience, but symbolic interactionism sees experience as our individually interpreted symbolic interactions situated within our social milieu, our social environment.

For example, in Harvey Molotch’s insightful introduction to the theory of symbolic interaction, the appearance of my neighbor at her doorstep (a symbolic gesture: “I am here”) triggers me to turn my just attempted swat at her friendly, but bothersome dog into a wave, into a greeting. The story shows how our actions are the result of our dynamic interpretation of signs in our social worlds and how we think others will receive our actions.

Signs and symbols stand for other things. Signs include anything we might encounter in our interactions with others including words, phrases, gestures, images, icons, artifacts of material culture, social structures, ideas, and any bundling of experience (whether live, imagined, or communicated). Symbolic interactionism is the idea that our thinking and acting is a product of our interpretations of these signs and symbols from our social milieu motivated by wanting to form a positive sense of self in the eyes of others, that is, motivated by our sense of dignity.

By emphasizing the interpretative role of the accumulation of our lifetime’s symbolic interactions, the theory gestures to the gulf that separates what happened from our thinking about it. Moreover, each of our interpretations can be seen as a fiction of relationship: we see the fictive role of interpreting symbolic interactions and its role in understanding the world of relationships in which we live.

At a societal level, symbolic interactionism indicates the value of the great traditions of inquiry and action. These traditions are the source of the symbolic meanings intimated in our interactions. Our interpreted interactions regenerate society by rearticulating and reevaluating the traditions that inform each symbolic interaction. As this process permeates each interaction of each person throughout society, the dynamic manifestation in our minds and in our behavior of our reinterpreted and hence reformulated traditions continually regenerates society.

By showing how these interpreted symbolic interactions so directly affect our minds, behavior, and society, the theory makes clear the value of learning from and curating the wisdom in humanity’s vast inventory of traditions of inquiry and action. It provides new insights into how our learning affects us and how that in turn changes the world.

To emphasize this point, it is the stories we tell ourselves and others about the great traditions that informs, and in fact forms, our minds, shapes our behavior, and molds our society. In this sense, these stories directly and profoundly shape the world despite the fact that most of us think changing the world is beyond our control. In fact, each of us changes the world with our every social interaction!

Now we can circumscribe the fundamental role of story in our lives:

- Story is the fiction of relationship which both forms the basis of our understandings (which are nothing but relationships) and forms the interpretations of our symbolic interactions.

- Story is the means by which the great traditions of inquiry and action are communicated from person to person and generation to generation.

- Story is the Truth of inquiry and wonder in our explorations.

- Story is the dynamic interpretation of meaning in our every symbolic interaction.

- Story is the way society regenerates itself built on the always reinterpreted and reformulated great traditions of inquiry and action. That is, story is the means through which the world changes.

- Finally, story is, for all the above reasons, a key tool for the comprehensivist as we strive to make sense of it all and of each other.

Does this circumscribe the fundamental role of story? What are the strengths and weaknesses in this characterization of the role of story? What fundamental role, if any, do you think story provides in our great traditions of inquiry and action, in our comprehensivity, and in our lives?

This essay was written to provide ideas in support of the 16 September 2020 session of “Comprehensivist Wednesdays” at 52 Living Ideas (crossposted at The Greater Philadelphia Thinking Society).

Addendum: The 1h 33m video from the 16 September 2020 event:

Read Other Resource Center Essays

- Humanity’s Great Traditions of Inquiry and Action

- The Necessities and Impossibilities of Comprehensivism

- The Comprehensive Thinking of R. Buckminster Fuller

- The Value of The Ethnosphere

- The Value of Multiple Working Hypotheses

- The Inductive Attitude: A Moral Basis for Science and Comprehensivism

- Mistake Mystique in Learning and in Life

- Rethinking Change and Evolution: Is Genesis Ongoing?

- How to Create That-Which-Is-Not-Yet

- How To Explore The Future (and Why)

- Redressing The Crises of Ignorance

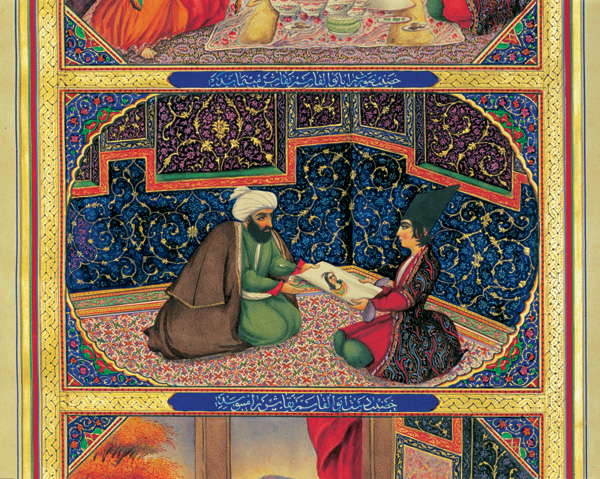

- Comprehensivism in the Islamic Golden Age

Stories in my thoughts are a collection of memories stored in the brain and then related and interrelated in the mind. Depending on 1’s circumstance fiction or fact.

Cj I like your thoughts and more important that you share them. Thank you Kelly

Story is retelling; what is “said about an event”. Definitely can GO RIGHT ALONG with that!

The words “creative” or “construct” conveys a lot of what you are getting at, but do you feel “fiction” is a better fit?

Possibly fiction means: construct or invention from imagination, but this begs the question of whether the definition should omit: “(in the sense of) in violation of a truth”. That is an essential question.

The source of the word fiction, with root meanings ”fashion, shaped, form, feign, ruse, dissimulate” hints not only at fooling the senses which covers the issue of making a past event enter into the present, but inherently at rendering an ‘untruth’.

For the concept at hand, it seems there are two choices both of which originate in invention or the imagination. One, to feign in order to convey the reality; the second, to deceive with the deceit of portraying falsely. The first more often is rendered a retelling, here a story; the latter more often is labeled as producing a fiction.

A story, in not being the experience per se, and in leaving out the “fullness” of the truth of experience, is not untruth. That claim takes the presumption of some Vast External True Objective Universe as the only Reality as the only truth to disclose, and pits it against and diminishes human thought, experience and telling of the human event depicted in Story, as though the difference is invalidating — as though, the positions of the leaves on the tree around me which aren’t captured in my story invalidate the truth of my recollected climbing that tree.

Yet why isn’t my story perfect? I am not convinced. Is it because it is told to an other, or because it is read by me years later? It can’t be merely because there are elements which can be added to it.

I am also discomforted by the connotation of untruth which you may wish to imply by the choice of the word “fiction”. I am not sure my experience and all of my memory and recollection of it deserves the label “untruth”. Again, can’t measure against some unreal standard “complete truth”.

Interesting challenging writing, CJ!

David,

Perhaps your discomfort would be relieved by realizing that it is in the interpretation where we judge the truthfulness of the ideas conveyed by a communication. That idea gives us a good reason to distinguish the constructs in a writing from its interpretations. So as an act of objectivity in reading, we might think of fiction as a construct or invention for communication unencumbered by its interpretations.

Your story isn’t perfect because its interpretations are always fluid: they change over time, they change depending on perspective. Moreover, nonfiction has no magical means of protection from authorial ruses, pretensions, deceits, half-truths, and the like. So nonfiction and fiction are both subject to the vexing issues of truths and untruths that you raise.

As a former student in Arnold Weinstein’s 2013 course “The Fiction of Relationship”, I am upholding the definition of “fiction” from that tradition of inquiry and action. Furthermore, since I wanted to integrate Weinstein’s “fiction of relationship” and Marina Warner’s “The Truth in Stories” in my essay, it would have been awkward to use a more analytically precise word for “fiction”. In addition, part of my purpose is to challenge the tyranny of our truth-based modes of storytelling.

Finally, one of my objectives in the essay is to support more readers in dealing with the sometimes fantastic constructs in the writing of R. Buckminster (“Bucky”) Fuller (I am organizing an October 14th topic on his book “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth”: see https://www.meetup.com/52LivingIdeas/events/twpxvrybcnbsb/ and https://www.meetup.com/thinkingsociety/events/273141321/). For that purpose, I want to prepare readers to wonder about and question Bucky’s assertions rather than getting upended by the sometimes mythological language. I hope my essay gives them practice in the kind of interpretive art that will be needed to more fully engage Bucky’s writings.

There is an interesting thread of commentary on “The Fundamental Role of Story in Our Lives” under my Facebook post on this essay.

The 16th September 2020 event last Wednesday revealed a couple of clarifications on nonfiction and the ineffable that are worth documenting.

Nonfiction is fictive

Let me clarify my thoughts about nonfiction. I do not mean to disparage nonfiction. I do mean to disparage the elitist and arrogant view that some kinds of storytelling necessarily deserve the privileged position of being more truthful than other kinds of stories.

Nonfiction stories are constructed; they are an invention of language. Given that the word fiction includes the connotation construct and invention, nonfiction is fictive, it is a fiction; it is also a fiction of relationship.

I am also saying, with full kudos to Marina Warner who taught me this (see her wonderful essay “The Truth in Stories”): fantasy, fairy tale, and mythology have a truth to them: the Truth of inquiry and wondering.

The nonfiction story is not reality itself, it is a story that attempts to represent aspects of reality that the author claims to be true from their perspective. The author may be biased, they may be mistaken, they may have written some misleading passages, they might be deliberately misleading or even lying. For all these reasons and more, nonfiction requires diligent interpretation.

Nonfiction and fiction are both literature: they are both communications that require interpretation. Neither has a privileged access to truth or to reality. Both can afford us access to some truths and aspects of reality if we interpret them judiciously.

The Ineffable

I argued that the ineffable, that which is incapable of being described, is beyond the reach of story. I have offered the working hypothesis that everything that is knowable is a tradition of inquiry and action. As a tradition, it must be communicable. Therefore, it must be describable. From this perspective, all that is knowable is communicable and describable. The ineffable is therefore beyond what we can know, beyond what we can tell stories about.

The evidence that Einstein and others have thoughts which they are unable to describe suggests that humans are capable of ineffable thoughts. Truths that cannot be described, cannot be communicated. So they are not part of our collective knowledge which is the inventory of the great traditions.

During the event, I speculated that there are things you and I might know, such as tacit knowledge, which we cannot describe. Maybe we cannot describe them because we didn’t put in sufficient effort, maybe we will catch one of these “cosmic fish” soon but the “aha” moment hasn’t yet arrived, maybe we are not poet enough to adequately describe them.

This suggests that what is knowable contains as a strict subset the great traditions of inquiry and action. That might suggest that the great traditions do not circumscribe all that we can know. Perhaps, but my perspective is that you and I are in dialogue, exploring, and collaborating to understand it all. So, I would suggest that the relevant knowledge for our effort to understand the world (and maybe even the most important part of our knowing in general) is that which becomes part of our cultural heritage, that which gets transmitted as a tradition, that which is regenerated in our symbolic interactions.

The word “ineffable” also suggests that there are truths which cannot be described no matter our effort or our skill with language. Since science is about what can be described, it seems to me that even the most advanced science of one billion years from now will still be unable to understand these ineffable aspects of Universe, if they exist. It is important to begin to understand the limitations of science: if truly ineffable truths exist, science will never be able to disclose them.

CJ – Yes I did read your opinion. Last week I drew the comparison of two stories – the dramatazation of Apollo 13 .vs. StarTrek. Let me try again. My name is David Dittemore. I think you will agree that I am a real person. There is a fictional character, Donald Duck. You could say that our names are similar. But I contend that I am non-fiction – or a story about me would be. And any story about Donald Duck would be fiction. I see a definite difference. Yes there are always inconsistencies in non-fiction stories, accounts or documentaries – but still they are about real people or real events. Your turn.